I’m not a 3- or 4-letter code

PRM, VIP, WCHC

You can listen to the main article in this newsletter (read by me).

Hello everyone,

Last week, I had a very important hospital appointment near London Bridge station. Everyone who follows me on Twitter knows I have had many failed assists for some time. When I arrived at London Bridge station, again, no one was at the train door to meet me.

My local station had indeed called ahead, but they used the term VIP, which is often used as an acronym for "disabled", or "visually impaired person,” or "very important person.” This is not an official term or acronym, but it's often used in railway and transport. My last failed assist is an excellent example of why it shouldn't.

In this case, the passengers stopped the train from closing the doors, and someone ran to a Network Rail staff member, who later told me they thought a blind person was coming because "VIP" was used. So, no ramp was ready, and Network Rail doesn't do ramps at London Bridge. He alerted the dispatcher, and it was all a bit of a panic.

PRM, VIP, WCHC

The use of acronyms or codes to refer to disabled customers, such as PRM (Passengers with Reduced Mobility), VIP (visually impaired person), or WCHC (Wheelchair User, needs an aisle chair), has become normal in travel and transport. But they can cause issues. They are not a very kind way to talk about customers. Who wants to be referred to as a 3- or 4-letter code? There are more respectful and inclusive approaches when talking about disabled customers.

Also, if you start in a new industry, all these acronyms can be quite confusing, and I don't think they help much. People pick up the wrong meaning, which causes misunderstandings.

Reducing a person to a 3- or 4-letter code is dehumanising. Using codes to talk to a customer or to avoid mentioning that the customer needs assistance is a problem.

I sometimes get called "a Charlie" when I'm flying. That's not much better. Charlie stands for C in the aviation alphabet. So, they use the name for the last C in WCHC. When the assistance team is delayed, the flight attendant sometimes shouts through the cabin, "We still have a Charlie here." Again, awkward. And do they really think I don't understand they're talking about me?

Disabled is not a bad word

While PRM, WCHC, WCHR, WCHS, etc., are official IATA codes in aviation, they are not part of the handover protocol in railway when someone needs assistance. However, acronyms on accessibility creep more and more into railway, especially VIP and PRM. VIP is often used for a "visually impaired person" when it stands for "very important person" in aviation and everywhere else. Or, it's used as "very important person" but as a euphemism for "disabled". So, if one person uses the acronym differently as the message recipient, this can cause a failed assist.

I can't emphasise enough that disabled is not a bad word. If you think it is, please ask yourself why you believe that. Even if staff don't want to say someone is disabled, the far better way is to say what assistance the passenger needs, e.g., a ramp, guidance through the station, or luggage assistance. This approach avoids communication issues because it clearly states what is required.

The use of acronyms in this way also shows the lack of training in how to speak to and about disabled customers appropriately. Being called VIP in this situation is not a compliment or flattering; it's just awkward.

A matter of empathy

The use of codes can also create a barrier between disabled customers and staff members. When staff members become used to referring to people by codes, it can distance them from the human aspect of their interactions. This detachment may result in less empathetic and less personalised service, as staff members might focus more on fulfilling a checklist of requirements associated with a code rather than engaging with the individual as a person.

Furthermore, these codes can promote the medical model of disability. With this way of thinking, the customer is the problem because they are disabled, not the environment, the step between the train and the platform, or the lack of accessibility of planes. Medical-model-based codes support the notion that disabilities are purely medical issues without acknowledging society's role in creating and removing barriers to inclusion.

Outdated, dehumanising, and counterproductive

Additionally, using codes can contribute to a sense of othering. Labelling disabled customers with codes creates a distinction between them and non-disabled customers, potentially reinforcing notions of "normal" versus "different."

By removing codes, we can foster a more inclusive environment that recognises the individuality of disabled customers. This shift benefits disabled people and promotes a more empathetic and person-centred approach to customer experience. The practice of referring to disabled customers by 3- or 4-letter codes is outdated, dehumanising, and counterproductive.

Some interesting links

A mother said she was "belittled" after asking a passenger to move his luggage, which was blocking a train's wheelchair space.

A report published by University College London has outlined the difficulties caused by so-called 'floating' bus stops for visually impaired people. The charity Guide Dogs are now calling for their rollout to be halted.

A deaf passenger is suing Frontier Airlines, claiming a gate attendant blocked them from catching their flight.

Something to read

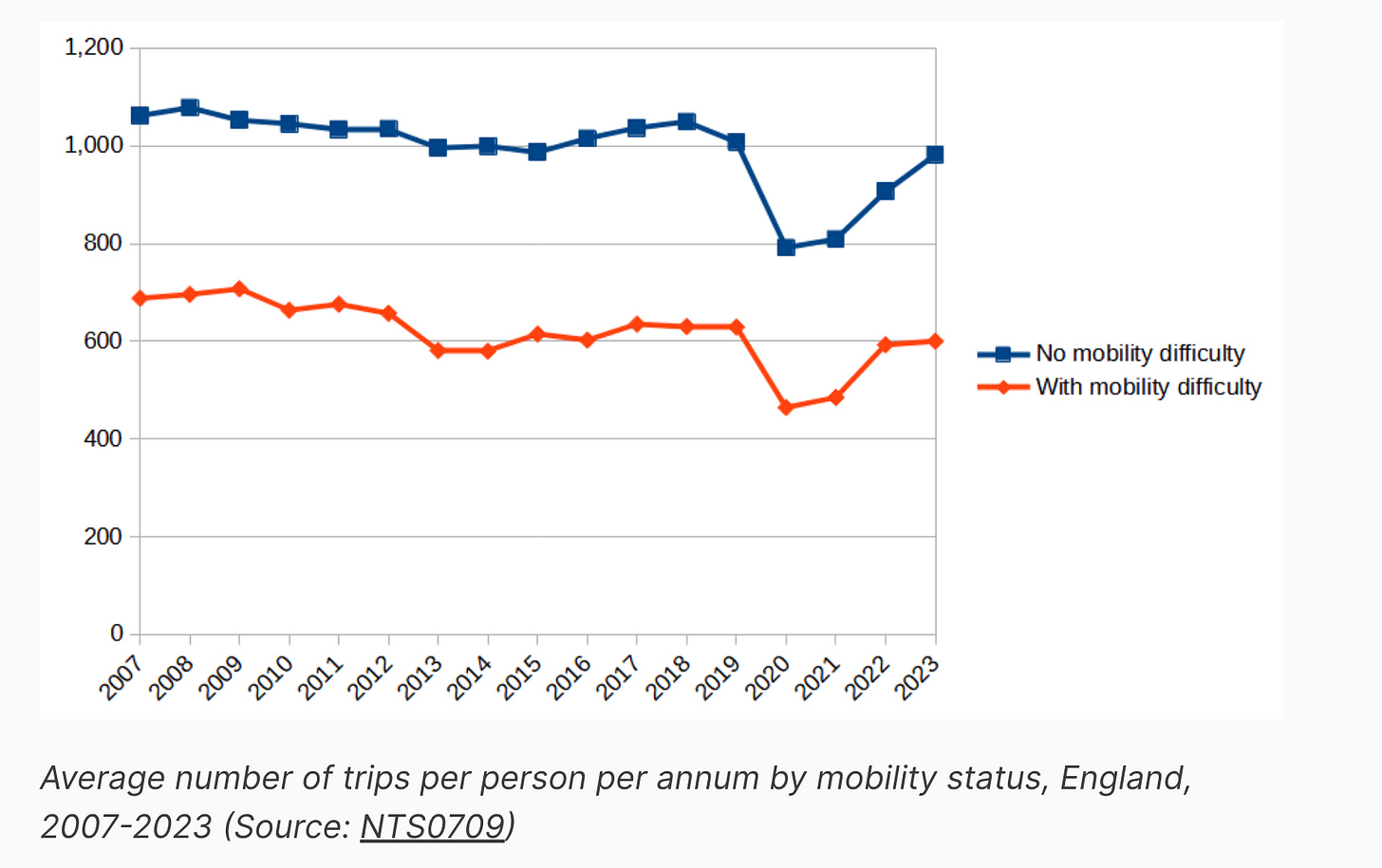

The National Travel Survey (NTS) covers personal travel in 2023 in England. The statistics show how and why people travel, as well as their vehicles and licences. People with mobility impairments have not recovered to the same extent as those without mobility impairments. James Gleave of Mobility Matters wrote a summary of the findings.

Some final words

The Accessible Link is a reader-supported publication. So, if you like what you’re reading, consider to

As a paid subscriber you will receive an additional edition every two weeks with best-practice tips on improving accessibility in your organisation.

Who is writing this newsletter?

I’m Christiane Link, and I improve the customer experience in aviation, transport, and travel. I worked as a journalist for over two decades and travelled extensively for business and leisure. I’m a wheelchair user.

Work with me

Whether you're a Customer service director, a Head of Customer Experience, a corporate Accessibility manager, a DEI leader, a transport planner, or a disabled employee resource group member, I can help you to make your organisation more inclusive. You can book me for speaking engagements or hire me as a consultant for your accessibility or DEI strategy, communications advice and other related matters. I have worked for airlines, airports, train operators, public transport providers, and companies in other sectors.

If you want to read more from me, follow me on LinkedIn, Twitter, Bluesky or Mastodon. You can also reply to this email if you want to contact me.

.